Uncovering the Sneaky Ways We Use Humor to Repress Emotions

It’s a common occurrence for humans to feel like our individual problems are absolutely the worst thing in the world, yet it’s just as common to feel like our problems aren’t as bad as someone else’s and therefore don’t merit the emotions we feel. In the past year or so, this phenomenon has been dubbed “First World Problems.”

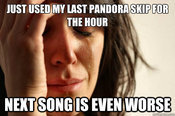

The result is a suite of hilarious videos and images cavorting around the ‘Net, ridiculing problems like “I’m so tired of eating at all the restaurants near work,” and “My TV show isn’t in HD.” The plus side of this is a healthy reality check, a reminder to “not take it so seriously.”

We should keep reading, watching, and making these hilarious memes—to remember not to take ourselves so seriously—but not take the ridicule too seriously either. Denial and attachment are two sides of the same coin.

The Problem with First World Problems

People use the idea of “first world problems” to heap guilt on top of their negative feelings. For example, John is frustrated he had to get a parking spot far from the entrance (a first world problem). Instead of dealing with the feeling of frustration, he represses it by labeling his problem “FWP.” Now he is frustrated and feels guilty for feeling frustrated. He shamed his emotion, a subtle way of saying to himself, “Your feelings don’t matter.” This is another way of saying, “You don’t matter,” which was probably unpinning the original feeling anyway. So John has not only swept the original unhappiness under the rug of conscious awareness, he has also just amplified it.

How do we avoid this? By treating ourselves, and our problems, like children who have skinned their knees. We as adults know the child will heal and be quickly over it, yet we also know that it seems like a big deal. A skinned knee actually does hurt. We don’t tell a four-year-old kid to “get over it.” We don’t ask them to make fun of themselves because a skinned knee isn’t as bad as children starving to death on a Pacific Island.

Why is a teenager’s breakup any less painful or deserving of love and care than a divorce, or a broken leg, abuse, or losing a job? If she experiences an immense amount of pain and sadness relative to herself, what difference does it make to judge her emotions against some purportedly objective scale? Does it help her? It either makes her feelings more valuable than they should be (if we buy too much into her story), or less valuable (if we tell her that she should get over it because at least she wasn’t abused).

Accept the Emotion, Deny the Justification

Everyone deserves love, compassion, and comfort in relation to their problems, regardless of what the problems are. Therefore all problems should be seen equally. Emotions by their very nature aren’t rational. They should almost never be judged because that only leads to repression, which means the emotion is never cleared away and leads us away from peace. John’s parking lot frustration is real and has to be dealt with regardless of the justification—whether it was a faraway parking spot or getting laid off.

Their justifications should be judged, however, because that kind of discernment leads us to deeper peace that is not contingent upon circumstances. Most people would agree that John’s justification for frustration in the parking lot is ridiculous. But is frustration at getting laid off any less ridiculous? There are countless examples of incredible success arising from seemingly terrible life changes—like when Steve Jobs got fired from his own company and went off to start Pixar.

The Best Thing

The best thing is to honor and find a healthy expression for the emotions, in ourselves and others, but let go of the justifications. Then we can open to the mystery, laugh at it all, and find joy in every situation.